Speakers at the Africa Financial Industry Summit’s fourth webinar identify the missing pieces for pension funds to bankroll more of the continent’s infrastructure needs and plug gaps left by the withdrawal of foreign capital.

By Kingsley Kobo

Africa’s pension fund sector has grown significantly over the past decade and a half, driven by an increasing population, a growing middle class and market reforms, according to the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Assets under management in Nigeria have reached $33bn; $12.8bn in Kenya; $12.1bn in Namibia and $9.7bn in Botswana, with South Africa having the largest on the continent at $500 billion.

But for these funds to contribute meaningfully to financing Africa’s infrastructure gaps, webinar participants believe the following actions are needed:

- Hiring dedicated specialists in infrastructure investments within pension funds

- Expanding pension coverage in informal sectors through digital channels

- Pooling more capital from multiple pension funds

Infrastructure investments: Expertise is lacking

The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that Africa needs between $130bn and $170bn of infrastructure spending each year to provide better roads, potable water, reliable power and stable internet for its population.

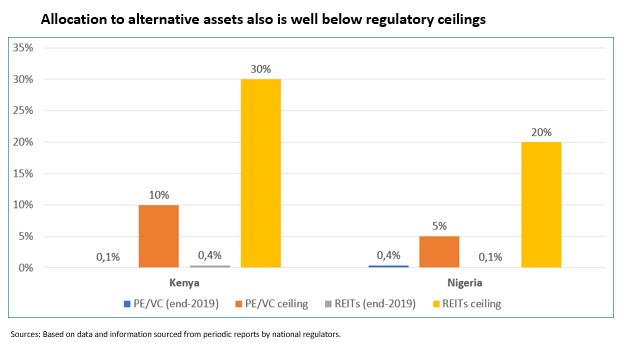

This presents huge investment opportunities in long-term development projects at a time when foreign capital inflows are drying up. However, pension fund managers are conservative in allocating capital to such alternative assets, opting instead for government and corporate bonds.

Ngatia Kirungie, head secretariat of Kenya Pension Funds Investment Consortium (KEPFIC), believes pension schemes are shying away from infrastructure projects because they do not understand how they work.

“Investment expertise has been lacking in pension schemes. If regulators allow them to hire different managers for different asset classes then you will have greater specialisation which will in turn yield better investment opportunities, resulting in lower risks and higher returns,” he said.

Informal sector coverage

Jacqueline Irving, senior economist at the International Finance Corporation (IFC), said: “For pension sectors and their economies to fully capitalise on opportunities, it will be important to accelerate reforms by enabling more extensive participation.” Extending pension coverage to the informal sector should be a priority,” she concluded.

Only 15% of Africans have pension coverage, far below the global average of 54%. However, extending coverage to the informal sector, which constitutes 80% of the continent’s workforce, is a mammoth task, all panelists acknowledged.

Designing products that enable informal sector workers to sign up for pension fund assets without complicated administrative procedures could help solve the puzzle, according to Oguche Agudah, CEO of the Pension Fund Operations Association of Nigeria (PenOp).

“In Nigeria, we have the ‘micro-pension product’ with lower fees designed for the informal sector. Anyone can subscribe using mobile phones and USSD codes. The product is bundled with other products that people use in their everyday lives,” he said. Similar products that allow people to subscribe anytime they wish also exist in Kenya.

Masha Maharaj, head of Securities Services Cluster, Sub Saharan Africa at Citi, believes that education and awareness can help spark more interest.

“We have to start empowering young people to understand the importance of pension fund building. We have to figure out what ways, from a digital perspective,” she said, particularly for those earning less than $2 to $5 per day.

Pooling resources

Investing in infrastructure projects involves significant capital, which could be an overwhelming challenge for individual pension schemes.

According to Ngatia: “Pooling could be a tool or solution to the size of the investment. By pooling resources from multiple pension schemes together, the capital need is significantly greater.”

However, pooled models, such as those in Kenya, currently operate only at national level and may not work in jurisdictions like Nigeria, where pension funds cannot invest offshore, Agudah of PenOp indicated.

Another potential setback to cross-border pooled funding is foreign exchange risk. Many African countries do not share a common currency, thus local pension funds need to convert into a hard currency while pooling resources.

“It increases uncertainty, which we always look to reduce. The returns you are seeking so desperately from these infrastructure opportunities could be eaten up by currency depreciation,” said Ngatia of Kenya’s KEPFIC.

What about green infrastructure?

Panelists also concurred that pension funds had to be conscious of Environmental, Social and Governance objectives in infrastructure investing.

But investments in green infrastructure projects are largely underexplored, with speakers suggesting it would require refined regulations and some time to pick up steam.

However, for Olano Makhubela, head of retirement funds supervision at South Africa’s Financial Sector Conduct Authority, the ESG component will be key for the future.

“It is fine having a good retirement benefit but there is no point retiring in a wasteland – a country with inequalities, a dysfunctional country or society. You won’t enjoy your benefits,” he said.

For further insights, you can watch the on-demand webinar ‘Strengthening Africa’s emerging pension fund sector’